A while ago, I wrote “Bye Opam, Hello Nix” where the topic of that post was that I replaced Opam with Nix as it works much better. This post is about taking this a bit further, discussing how I use Nix for local development, testing, and building Docker images.

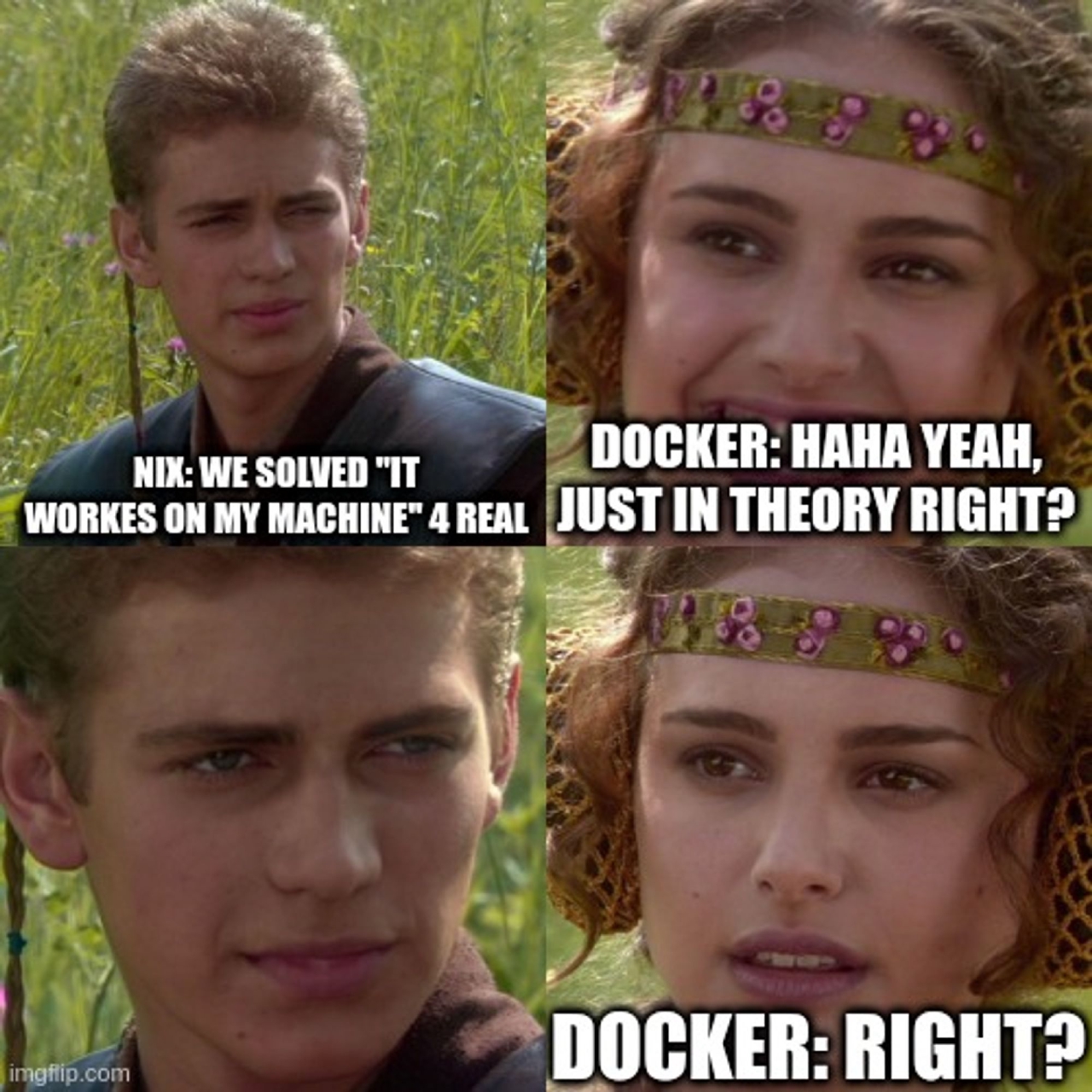

The core concept of Nix is “reproducible builds,” which means that “it works on my machine” is actually true. The idea of Nix is that you should be able to make an exact copy of something and send it to someone else’s computer, and they should get the same environment. The good thing about this is that we can extend it further to the cloud by building Docker images.

Even if Docker’s goal was to also solve the “it works on my machine” problem, it only does so to a certain level as it is theoretically possible to change the content of a tag (I guess that you also tag a new latest image ;) ? ) by building a new image and pushing it to the same tag.

Another thing I like about Nix is that it allows me to create a copy of my machine and send it to production. I can create layers, import them using Docker, and then tag and push them to my registry.

This specific post was written after working with and using Nix at work. However, the code in this post won’t be work-related, but I will show code that accomplishes the same task in OCaml instead of Python.

The problems I wanted to solve at work were:

- Making it easy for our data team to develop in a shared project.

- Being able to create a copy of my machine and move it to the cloud.

- Making it easier for us in CI and CD steps by preventing CI failures due to missing tools not being installed on the runner, and so on.

In this article, we will create a new basic setup for an OCaml project using Nix for building and development. The initial code will be as follows, and it will also be available at https://github.com/emilpriver/ocaml-nix-template

| |

The code in this Nix config is for building OCaml projects, so there will be OCaml related code in the config. However, you can customize your config to suit the language and the tools you work with.

The content of this config informs us that we can’t use the unstable channel of Nix packages, as it often provides us with newer versions of packages. We also define the systems for which we will build, due to Riot not supporting Windows. Additionally, we create an empty devShells and packages config, which we will populate later. We also specify the formatter we want to use with Nix.

It’s important to note that this article is based on nix flakes, which you can read more about here: https://shopify.engineering/what-is-nix

Development environment

The first thing I wanted to fix is the development environment for everyone working on the project. The goal is to simplify the setup for those who want to contribute to the project and to achieve the magical “one command to get up and running” situation. This is something we can easily accomplish with Nix.

The first thing we need to do is define our package by adding the content below to our flake.nix.

| |

Here, I tell Nix that I want to build a dune package and that I need Riot, which is added to inputs:

| |

This also makes it possible for me to add our dev shell by adding this:

| |

So, what we have done now is that we have created a package called “nix_template” which we use as input within our devShell. So, when we run nix develop, we now get everything the nix_template needs and we get the necessary tools we need to develop, such as LSP, dune, and ocamlformat.

This means that we are now working with a configuration like this:

| |

Running tests

When working with Nix, I prefer to use it for running the necessary tools both locally and in the CI. This helps prevent discrepancies between local and CI environments. It also simplifies the process for others to run tests locally; they only need to execute a single command to replicate my setup. For example, I like to run my tests using Nix. It allows me to run the tests, including setting up everything I need such as Docker, with just one command.

Let’s add some code into the packages object in our flake.nix.

| |

In the code provided, we create a new package named test. This executes dune runtest to verify our code. To run our tests in the CI or locally, we use nix build '#.packages.x86_64-linux.test. This method could potentially eliminate the need for installing tools directly in the CI and running tests, replacing all of it with a single Nix command. Including Docker as a package and running a Docker container in the buildPhase is also possible.

This is just one effective method I’ve discovered during my workflows, but there are other ways to achieve this as well.

Additionally, you can execute tasks like linting or security checks. To do this, replace dune runtest with the necessary command. Then, add the output, such as coverage, to the $out folder so you can read it later.

I have tried to use Nix apps for this type of task, but I have always fallen back to just adding a new package and building a package as it has always been simpler for me.

Building for release

So, time for building for release and this is the part where we make a optimized build which we can send out to production. How this works will depend on what you want to achieve but I will cover 2 common ways of building for release which is either docker image or building the binary.

Building the Binary

To enable binary building, we only need to add a buildPhase and an installPhase to our default package used for building. This makes our definition appear as follows:

| |

This implies that when we construct the project using nix build '#.packages.x86_64-linux.default', we are building the project in an isolated sandbox environment and returning only the required binary. For example, the result folder now includes:

| |

Here, main.exe is the binary we built.

Building a docker image

Another way to achieve a release is by building a docker image layers using nix that we later import into docker to make it possible to run it. The benefit of this is that we get a reproducible docker as we don’t use Dockerfile to build our image and that we can reuse a lof of the existing code to build the image and the way we achieve this is by creating a new package where I in this case call this dockerImage

| |

And to build our docker image now do we simply only need to run

| |

And we can later on load the layers into docker

| |

Afterwards, we can tag the image and distribute it. Quite convenient.

There are some tools specifically designed for this purpose, which are very useful. For example, skopeo can be used to tag and push an image to a container registry, such as in a GitHub action.

| |

What Nix does when building a Docker image is that it replaces the Docker build system, often referred to as Dockerfile. Instead, we build layers that we then import into Docker.

Adding a library that don’t exist on nix packages

Not all packages exist on https://search.nixos.org/packages, but it’s not impossible to use that library if it doesn’t. Under the hood, all the packages on the Nix packages page are just Nix configs that build projects, which means that it’s possible to build projects directly from source as well. This is how I do it with the random package below:

| |

This now allows me to refer to this package in other packages to let Nix know that I need it and that it needs to build it for me.

Something to keep in mind when you fetch from sources is that if you use something such as

builtins.fetchGit, you use the host machine’s ssh-agent whilepkgs.fetchFromGitHubuses the sandbox environment’s ssh-agent if it has any. This means that some requests don’t work unless you either use something likebuiltins.fetchGitor add your ssh config during the build step.

The final flake.nix

After all these configurations, we should now have a flake.nix file that matches the code below

| |

This code also exist at github.com/emilpriver/ocaml-nix-template

The end

I hope this article has helped you with working with Nix. In this post, I built a flake.nix for OCaml projects, but it shouldn’t be too hard to replace the OCaml components with whatever language you want. For instance, packages exist for JavaScript to replace NPM and Rust to replace Cargo.

These days, I use Nix for the development environment, testing, and building, and for me, it has been a quite good experience, especially when working with prebuilt flakes.

My goal with this post was just to show “a way” of doing it. I’ve noticed that the Nix community tends to give a lot of opinions about how you should do things in Nix. The hard truth is that there are a lot of different ways to solve the same problem in Nix, and you should pick a way that suits you.

If you like this type of content and want to follow me to get more information on when I post stuff, I recommend following me on Twitter: https://x.com/emil_priver