According to my Linkedin profile, I have been writing code for a company for almost 6 years. During this time, I have worked on PHP and Wordpress projects, built e-commerce websites using NextJS and JavaScript, written small backends in Python with Django/Flask/Fastapi, and developed fintech systems in GO, among other things. I have come to realize that I value a good type system and prefer writing code in a more functional way rather than using object-oriented programming. For example, in GO, I prefer passing in arguments rather than creating a struct method. This is why I will be discussing OCaml in this article.

If you are not familiar with the language OCaml or need a brief overview of it, I recommend reading my post OCaml introduction before continuing with this post. It will help you better understand the topic I am discussing.

Hindley-Milner type system and type inference

Almost every time I ask someone what they like about OCaml, they often say “oh, the type system is really nice” or “I really like the Hindley-Milner type system.” When I ask new OCaml developers what they like about the language, they often say “This type system is really nice, Typescript’s type system is actually quite garbage.” I am not surprised that these people say this, as I agree 100%. I really enjoy the Hindley-Milner type system and I think this is also the biggest reason why I write in this language. A good type system can make a huge difference for your developer experience.

For those who may not be familiar with the Hindley-Milner type system, it can be described as a system where you write a piece of program with strict types, but you are not required to explicitly state the types. Instead, the type is inferred based on how the variable is used. Let’s look at some code to demonstrate what I mean. In GO, you would be required to define the type of the arguments:

| |

However, in OCaml, you don’t need to specify the type:

| |

Since print_endline expects to receive a string, the signature for hello will be:

| |

But it’s not just for arguments, it’s also used when returning a value.

| |

This function will not compile because we are trying to return a string as the first value and later an integer. I also want to provide a larger example of the Hindley-Milner type system:

| |

The signature for this piece of code will be:

| |

In this example, we create a new module where we expose 3 functions: make, print_car_age, and print_car_name. We also define a type called car. One thing to note in the code is that the type is only defined once, as OCaml infers the type within the functions since car is a type within this scope.

OCaml playground for this code Something important to note before concluding this section is that you can define both the argument types and return types for your function.

| |

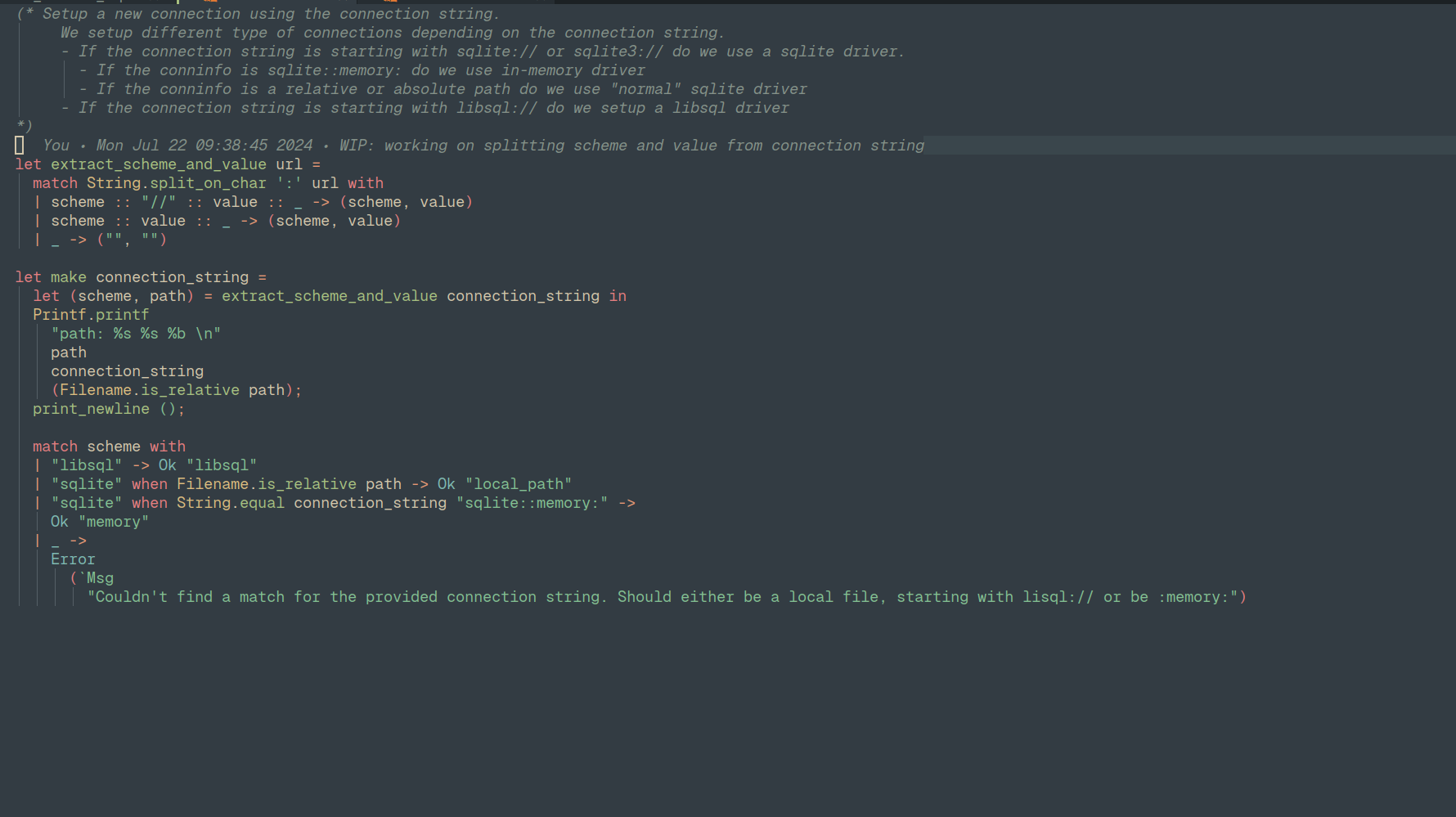

Pattern matching & Variants

The next topic is pattern matching. I really enjoy pattern matching in programming languages. I have written a lot of Rust, and pattern matching is something I use when I write Rust. Rich pattern matching is beneficial as it eliminates the need for many if statements. Additionally, in OCaml, you are required to handle every case of the match statement.

For example, in the code below:

| |

In the code above, I am required to include the last match case because we have not handled every case. For example, what should the compiler do if the name is Adam? The example above is very simple. We can also match on an integer and perform different actions based on the number value. For instance, we can determine if someone is allowed to enter the party using pattern matching.

| |

But the reason I mention variants in this section is that variants and pattern matching go quite nicely hand in hand. A variant is like an enumeration with more features, and I will show you what I mean. We can use them as a basic enumeration, which could look like this:

| |

This now means that we can do different things depending on this type:

| |

But I did mention that variants are similar to enumeration with additional features, allowing for the assignment of a type to the variant.

| |

Now that we have added types to our variants and included HavePets, we are able to adjust our pattern matching as follows:

| |

We can now assign a value to the variant and use it in pattern matching to print different values. As you can see, I am not forced to add a value to every variant. For instance, I do not need a type on HavePets so I simply don’t add it.

I often use variants, such as in DBCaml where I use variants to retrieve responses from a database. For example, I return NoRows if I did not receive any rows back, but no error.

OCaml also comes with Exhaustiveness Checking, meaning that if we don’t check each case in a pattern matching, we will get an error. For instance, if we forget to add HavePets to the pattern matching, OCaml will throw an error at compile time.

| |

Binding operators

The next topic is operators and specific binding operators. OCaml has more types of operators, but binding operators are something I use in every project.

A binding could be described as something that extends how let works in OCaml by adding extra logic before storing the value in memory with let.

I’ll show you:

| |

This code simply takes the value “Emil” and stores it in memory, then assigns the memory reference to the variable hello. However, we can extend this functionality with a binding operator. For instance, if we don’t want to use a lot of match statements on the return value of a function, we can bind let so it checks the value and if the value is an error, it bubbles up the error.

| |

This allows me to reduce the amount of code I write while maintaining the same functionality.

In the code above, one of the variables is an Error, which means that the binding will return the error instead of returning the first name and last name.

It’s functional on easy mode

I really like the concept of functional programming, such as immutability and avoiding side-effects as much as possible. However, I believe that a purely functional programming language could force us to write code in a way that becomes too complex. This is where I think OCaml does a good job. OCaml is clearly designed to be a functional language, but it allows for updating existing values rather than always returning new values.

Immutability means that you cannot change an already existing value and must create a new value instead. I have written about the Concepts of Functional Programming and recommend reading it if you want to learn more.

One example where functional programming might make the code more complex is when creating a reader to read some bytes. If we strictly follow the rule of immutability, we would need to return new bytes instead of updating existing ones. This could lead to inefficiencies in terms of memory usage.

Just to give an example of how to mutate an existing value in OCaml, I have created an example. In the code below, I am updating the age by 1 as it is the user’s birthday:

| |

What I mean by “it’s functional on easy mode” is simply that the language is designed to be a functional language, but you are not forced to strictly adhere to functional programming rules.

The end

It is clear to me that a good type system can greatly improve the developer experience. I particularly appreciate OCaml’s type system, as well as its option and result types, which I use frequently. In languages like Haskell, you can extend the type system significantly, to the point where you can write an entire application using only types. However, I believe that this can lead to overly complex code. This is another aspect of OCaml that I appreciate - it has a strong type system, but there are limitations on how far you can extend it.

I hope you enjoyed this article. If you are interested in joining a community of people who also enjoy functional programming, I recommend joining this Discord server.