“Initial Commit” is a series of posts where I explore different topics that interest me. In this post, we will look at Zig.

Recently, I overheard a conversation at work about the programming languages Rust and Zig. Later that evening, I stumbled across the Twitch streamer kristoff_it. Loris, the VP of Community in the Zig language, was working on auto-documentation for the Zig language, which caught my interest. So, I decided to look into it further.

Zig is a programming language that has been around for a while, and I thought it would be a good idea to check it out. Although still in development, Zig has some interesting features. However, there is still a lot of work to be done before its first stable release, but progress is being made. Although there is still work to be done before the 1.0 release, there are some companies that have started to adopt Zig, such as Uber. Uber recently released an article about using Zig for its infrastructure, indicating an interest in the language.

Since Zig is in its early stages, it lacks some features that would be beneficial to have, such as documentation for everything to explain how things work. I feel that this is something that is currently missing and would greatly appreciate seeing more of it. However, this is currently under development.

Zig: The programming language

Zig is a relatively new programming language, designed by Andrew Kelly, that first appeared on February 8, 2016, according to Wikipedia. This is a general-purpose language that aims to provide a balance between performance, safety, and ease of use. One of its main goals is to be a better alternative to C, compared to Rust which aims for the C++ world. Zig also aims to prevent hidden control flows that may cause your code to run unintended functions.

Zig has four different modes for compiling code: Debug, ReleaseFast, ReleaseSafe, and ReleaseSmall. You can read more about them here. These modes can be applied to different scopes with various combinations, allowing you to modify the settings in your code and apply them to different functionalities.

| |

Functions prefixed with a @ are provided by the Zig language.

Zig’s Unique Approach to Building Applications

Zig has a different way of handling builds than what I’ve seen before. To create a new project, you first create a new folder, enter that folder, and run zig init-exe. This creates a src folder and a file named build.zig, which is used to tell Zig how to build your application.

And the output from the above command in the build.zig file mostly looks like this (Zig is still in development, so the output may differ in different versions of Zig.):

| |

Defining how to build your code this way is not something I’ve experienced earlier. I believe it is not essential to elaborate on every aspect of this code. However, if you wish to acquire more knowledge regarding the build step, I highly recommend referring to this guide on zig.news. In brief, we specify the target operating system and build mode. Then, we instruct Zig to register and compile a new executable called fresh, with it’s main file located at src/main.zig. We also tell Zig to install all code dependencies we need.

Finally, we register a run command with the description “Run the app”, which we can use when building our code.

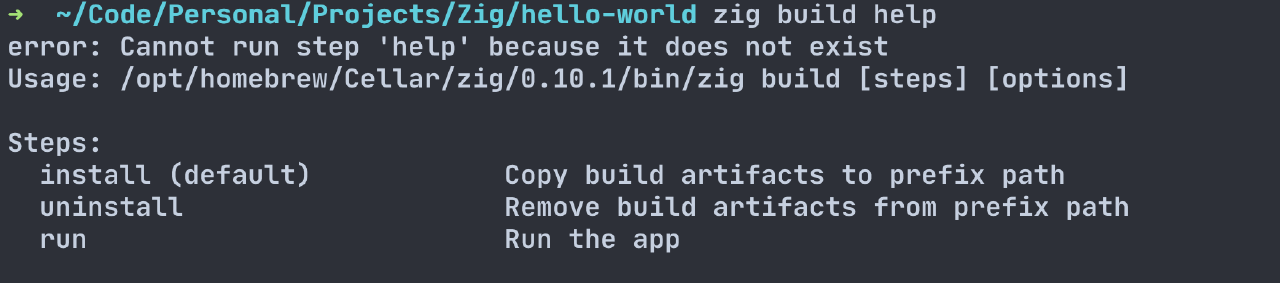

After registering the “run” command, we can verify whether we are running “zig build XXX”, where XXX is not a registered word and would cause an error. This command can also be run directly by executing zig build run.

This means that we can register different commands that suit each application. While this functionality may not be uncommon, it’s nice to have the ability to customize the build depending on logic in the code and handle it through code.

Integrating C code in Zig applications

A useful feature of Zig is the ability to import C code directly using the @cImport() and @cInclude() annotations. This allows us to include libraries such as curl/curl.h in our Zig applications.

| |

Running the code above won’t work. It’s a stripped-down example from the code-examples

Zig Syntax

Most of the content in this section of the article comes from https://ziglearn.org/chapter-1/. This section of the post contains interesting information that I haven’t seen before in other languages, and I thought it would be good to write about.

Arrays

Zig allows you to define the length of an array, or not define it at all. To not define the length, add an underscore (_) to the array declaration. For example, creating an array without a defined length looks like this:

| |

And creating an array with a defined length looks like this:

| |

Loops

Zig also provides a good syntax for loops that I personally like. Zig defines its loops with a condition and then values.

| |

When using for loops, you can define which fields you want to use inside the loop. For example, if you want to iterate over a for loop and have the index for each loop, you can define your code like this:

| |

If you only care about the array value you are currently working with and not the index, you can define your for loop like this:

| |

Switch

I am familiar with Zig’s switch statements and personally like them. They share similarities with Rust’s switch statements, such as the need to handle every edge case or use a default “else” clause. This means that if there are five different edge cases and only two of them are handled, the “else” clause will handle the rest of the cases. Switching on enums, unions, and so on is also allowed. However, Zig allows you to use switch outside of functions and assign values to a const. For example, you can use the value inside of functions. An example of this type of switch statement is switching on which OS the user is using and displaying different messages.

| |

Example taken from Zig docs

Zig Error Handling

Zig’s error handling mechanism uses an enum called “error set”. At compile time, each variant of the enum is assigned an integer greater than 0 that is used to identify the error message displayed to the user. If you declare the same error set multiple times, the variants will be assigned the same integer values. I see Zig error handling as similar to how Golang handles errors: as values with which we can work.

Developers familiar with Rust may be familiar with the Result<T, Error> return type for error handling. In contrast, Zig returns the type Error!u64.

As an example, let’s say we create the following error set:

| |

We can then use this error set in a function that returns the error type FileOpenError!u64. If this function returns the OutOfMemory error, Zig would return the error value FileOpenError2.

However, Zig has more to offer than just this. The compiler automatically adds all error tags to an anyerror type. This allows you to specify that a function can either return a specific error tag or anyerror. Each caller of a function can handle specific errors but must also include an else statement in its switch statements to handle any unexpected errors. All error tags from all functions used anywhere in the codebase are automatically collected to form the contents of the anyerror enum.

Zig’s “try/catch” keyword

Zig has a cool feature called try that can be used in front of a function to catch errors and return them easily. For example:

| |

If this function fails to parse the input string, it will return an error that we can work with. If it parses the value without any errors, it will continue with the rest of the code. try is a shorthand for catch |err| return err. In the code example above, this would be:

| |

As you can see in this example, there is a catch keyword which is part of Zig’s error handling. Being able to do logic if we get an error with Zig is easy. For example, if we want to assign a default number if it fails, we can do so via:

| |

We can run functions or return values if our code breaks as well:

| |

Ending

I hope you enjoyed reading this post. It covers some of the topics that I found most interesting when I first looked into Zig. My thoughts on Zig may change in the future, but for now, here are some links that you might find useful when exploring Zig. 😄 I’m looking forward to seeing how Zig improves in the future.

Also, If you want to talk about this post did I post it on Reddit

Awesome Zig

https://github.com/C-BJ/Awesome-Zig

This repository contains useful links and projects that could help you with your development.

Zig LSP

https://github.com/zigtools/zls

Zig’s Language Server Protocol. I recommend using the latest release and matching your Zig version with the ZLS version.

Zig News

This is a forum for Zig-related articles.

What is Zig’s Comptime? by Loris Cro

https://kristoff.it/blog/what-is-zig-comptime/

This article explains comptime in Zig.

Zig build explained

https://zig.news/xq/zig-build-explained-part-1-59lf

This is a series of three posts that explains Zig’s build system. I found it to be helpful for understanding the build system in Zig.

Bun.sh

Run, test, transpile, and bundle JavaScript & TypeScript projects — all in Bun. Bun is a new JavaScript runtime built for speed, with a native bundler, transpiler, test runner, and npm-compatible package manager baked-in. Built in Zig.